Nonprofit Hosting Third Annual Overnight Relay Run to the Sun Relay – April 20-21, 2013

Beyond Batten Disease Foundation is pleased to announce its 3rd Annual Run to the Sun Relay that will take place April 20-21. Run to the Sun is an overnight, long distance relay that begins at Enchanted Rock State Park and ends at Laguna Gloria in Austin, Texas. This event has opportunities for both runners and non-runners and is sure to be a great experience for all.

25 to 30 teams of five to 10 advocates will run over 90 miles throughout the night to raise money and awareness for Batten disease. Each relay team is working together to raise $5,000 to benefit Beyond Batten Disease Foundation in their quest to accelerate research and find a cure for Batten disease. The race starts at Enchanted Rock the afternoon of Saturday, April 20th and the finish line will be a celebration breakfast with food and entertainment. Runners, volunteers and supporters will stand together at sunrise while we celebrate the strength and determination of those impacted by Batten disease.

The relay race consists of 15 legs. Relay teams will meet their runners at exchange stations at the end of each leg to “pass the baton” to the next runner. This year, for the first time, each leg of the relay race will be dedicated to a child affected by Batten disease. Teams will have the opportunity to read biographies and view photos of each child as a way to get to know the children they are running for.

For those who don’t consider themselves runners, but still wish to participate, Run to the Sun has plenty of opportunities to be involved. Over 120 volunteers are needed to help the race run smoothly. Volunteer groups are needed to run the exchange stations that will serve as a place for teams to gather and support their runners at the end of each leg. Volunteers are also needed to help with set-up and tear-down, route support and start and finish activities.

Another way to participate with Run to the Sun Relay is through a sponsorship. Run to the Sun relay is still in need of sponsors for the starting line and each of the exchange stations. In return for their generosity, sponsors receive branding and recognition on all marketing and communication collateral, on-event signage, the Run to the Sun website, media exposure and more.

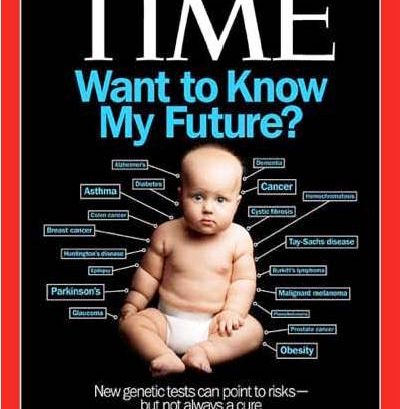

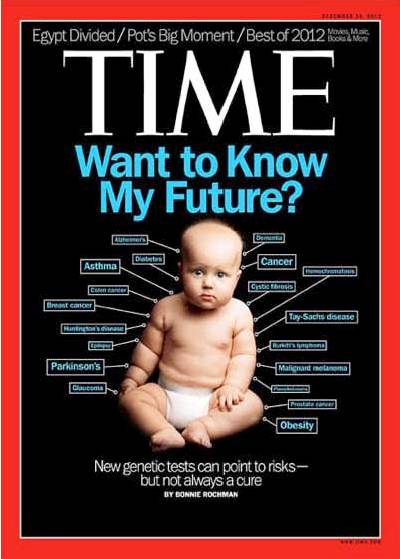

Batten disease is an inherited, neurological degenerative disorder that primarily affects children. It strikes without warning, starting with vision loss and seizures, progressively impairing the child’s cognitive and motor capacities, and ultimately takes their lives. It is difficult to image a worse fate for a child, but with your leadership and support there is hope. Join us in our mission to find a cure. For many families, this is truly a race against time.

To learn more about getting involved with the race, either as a runner, volunteer, sponsor, or just to make a donation, please visit www.runtothesunrelay.com. If you have any questions, please contact Rachel Armbruster at 512-944-3417 or runtothesun@beyondbatten.org.

For more information about Batten disease and Beyond Batten Disease Foundation, please visit www.beyondbatten.org.