Juvenile Batten (CLN3) disease is an ultra-rare disease whose early symptoms can be difficult for parents, teachers, pediatricians, opthalmologists, or neurologists to detect. Affected children may be unaware that their vision isn’t normal and adaptations such as sitting closer to the television or board at school, or struggling with learning to read, do not trigger alarm bells. When a problem is suspected, the first specialized care physician is usually an optometrist or ophthalmologist who, most likely, has never had a patient with this disease. Retinal thickness is still intact and lipofuscin protein and lipid deposits on the back of the retina can be difficult to see early-on.

Symptoms

Most children with juvenile Batten disease experience the following symptoms in the following and sometimes overlapping order. However, each child is different so the exact onset, severity, or even the presence of certain symptoms cannot be predicted.10

- Progressive vision loss in previously healthy children between 5 and 10 years old,

- Subtle to more pronounced personality and behavioral changes beginning at age 6,

- Seizures usually begin about 8 years old but can develop at any time during the disease,

- Intellectual decline seen as the inability to keep up with classmates,

- Echolalia (repetitive speech). For example, if a parent says, “It’s time for a bath,” the child may repeat, “for a bath” once or several times without recognizing that it is happening,

- Loss of speech,

- Motor problems – lack of muscle coordination, slowness of movement, tremor, rigidity and postural instability ,

- Dementia, Psychosis and sometimes hallucinations can appear and disappear at any time,

- Potential cardiac involvement in the late teens to early 20s,

- Premature death in the late teens to early or mid-20s.

Diagnostic Tests*

The following tests are often used in combination with one another and diagnose CLN3 and other forms of Batten disease:

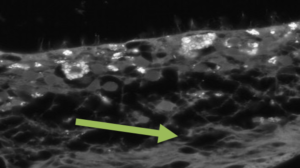

- Flourescent deposits

Photo courtesy of Bozorg S, Ramirez-Montealegre D, Chung M, Pearce DA. Flourescent deposits in juvenile Batten (CLN3) disease retina. Juvenile Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (JNCL) and the Eye. Surv Opthalmol. 2009. Jul-Aug;54(4):463-471.

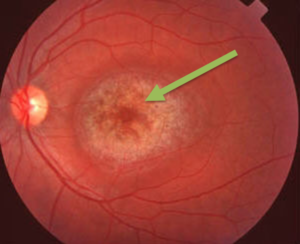

“Bull’s Eye” – Photo courtesy of Sachev A and Scotcher S. Batten’s disease presenting as visual loss in twins. Arch Dis Child. 2019. Sep;104(9):843.

The accumulation of autoflourescent ceroid lipofuscin deposits throughout the body is a hallmark sign of CLN3 and other forms of Batten disease. These deposits can sometimes be detected by visually examining the back of the eye. Over time, deposits appear more pronounced, retinal thickness is reduced and circular bands of different shades of pink and orange at the optic nerve and retina appear at the back of the eye. Doctors call this a “bull’s eye.”10,16

- Visual Evoked Potentials and Electroretinograms. These are recordings of abnormal electrical signals in the visual processing center of the brain.9,16..

- Blood tests

Vacuolated lymphocytes (white blood cells) are found in metabolic disorders such as juvenile Batten disease.4,8 - Urine tests

These tests can detect the presence of elevated levels of long chain, mostly unsaturated organic compounds, called dolichols. Dolichols can be found in the urine of many patients with Batten and other metabolic diseases.7,15. - Skin or tissue sampling

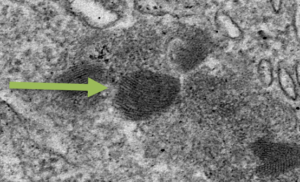

“Fingerprint Deposits” (Photo courtesy of Michela Palmieri 2013)

The accumulation of ceroid lipofuscin deposits throughout the body is a hallmark sign of Lysosomal Storage Diseases. These deposits can be detected by viewing skin cells under a microscope and in some cases, by visually examining the back of the eye. In general, these deposits resemble fingerprints.10,16

- Electroencephalogram (EEG)

An EEG records electrical activity in the brain through electrode patches placed on the scalp. Physicians use painless and noninvasive EEGs to look for telltale signs of seizures typical of juvenile Batten disease.1. - Brain scans

Imaging can help doctors look for changes in the brain’s appearance. Two commonly used imaging techniques are computed tomography(CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Both are sophisticated technologies that help detect whether certain brain areas are shrinking in children with juvenile Batten disease.2,11 - *DNA analysis

Screening one’s DNA blueprint obtained from blood, saliva or skin can find mistakes in the CLN3 gene responsible for juvenile Batten disease.

*There can often be difficulty seeing some of the signs described above. For example, vacuolated lymphocytes and dolichols may be present at levels too low to detect in blood or urine. The only definitive diagnosis for genetic diseases like CLN3 or other forms of Batten is a DNA test.5

What to do if you suspect your child has juvenile Batten disease?

References

- Arntsen V, Strandheim J, Helland IB, et al. Epileptological aspects of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (CLN3 disease) through the lifespan. Epilepsy Behav. 2019. May;94:59-64.

- Autti TH, Hamalainen J, Mannerkoski M, et al. JNCL patiets show marked brain volume alterations on longitudinal MRI in adolescence. J Neurol. 2008;255:1226

- Bozorg S, Ramirez-Montealegre D, Chung M, et al. Juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL) and the eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009 Jul-Aug;54(4):463-71.

- Collins J, Holder GE, Hebert H, et al. Batten disease: features to facilitate early diagnosis. Br J Opthalmol. 2006. Sep;90(9):1119-24.

- Cotman SL, Karaa A, Staropoli JF, et al. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis: impact of recent genetic advances and expansion of the clinicopathologic spectrum. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013 Aug;13(8):366

- Gainotti S, Mascalzoni D, Bros-Facer V, et al. Meeting Patients’ Right to the Correct Diagnosis: Ongoing International Initiatives on Undiagnosed Rare Diseases and Ethical and Social Issues. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018. Sep 21;15(10).

- Kimura S and Goebel HH. Light and Electron Microscopic Study of Juvenile Ceroid-Lipofuscinosis Lymphocytes. Pediatr Neurol. 1988;4(3):148-152.

- Kohlschütter A, Williams RE, Goebel HH, et al. The Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinoses (Batten Disease). 2nd Oxford University Press; c2011. Chapter 3, NCL Diagnosis and Algorithms; p. 24-34.

- LarsenA, Sainio K, Aberg, L. et al. Electroencephalography in juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis: visual and quantitative analysis. Eur J Paediatric Neur. 2001;3(Suppl. A): 179-183.

- Ostergaard, JR. Juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (Batten disease): current insights. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis. 2016. Aug 1:6:73-83.

- Rinne JO, Ruottinen HM, Nagren K, et al. Positron emission tomography shows reduced striatal dopamine D1 but not D2 receptors in juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Neuropediatrics. 2002;33:138-141.

- Sachev A and Scotcher S. Batten’s disease presenting as visual loss in twins. Arch Dis Child. 2019. Sep;104(9):843.

- Shire HGT. Rare Disease Impact Report [Internet]. 2013 Apr. Available from: http://www.rarediseaseimpact.com.

- Tokola AM, Salli EK, Aberg LE, et al. Hippocampal volumes in juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis: a longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. Pediatr Neurol 2014. Feb;50(2):158-63.

- Wolfe LS, Gauthier S, Haltia M, et al. Dolichol and dolichyl phosphate in the neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses and other diseases. Am J Med Genet Suppl. 1988;5:233-242.

- Wright GA, Georgiou M, Robson AG, et al. Juvenile Batten Disease (CLN3): Detailed Ocular Phenotype, Novel Observations, Delayed Diagnosis, Masquerades, and Prospects for Therapy. Opthalmol Retina 2019. Nov 13.

One thought on “Diagnosis/Symptoms”